‘Searching for the spirit and the sound’: A conversation with Pat Metheny

The ever-evolving Metheny comes to Buffalo for a stop on his ‘Dream Box’ tour

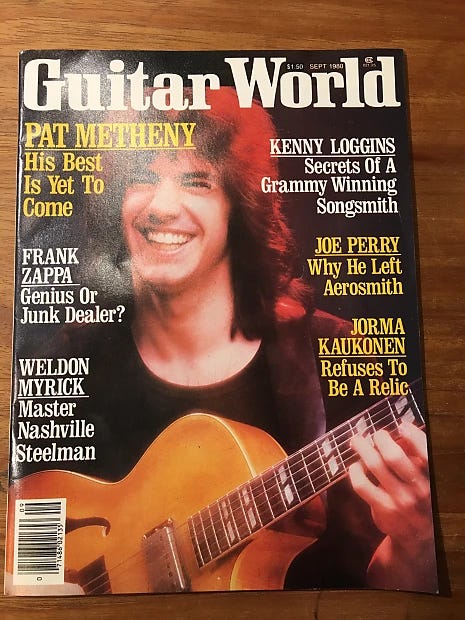

It was the September, 1980 issue of Guitar World Magazine that did it to me.

I had just turned 13, and was deep into my obsession with music in general, and the guitar in particular. My older cousin Mike was a guitarist, and I revered him, so during a family holiday get-together the previous November, I did what I always did - picked his brain about the tunes he was into. At the time, that meant Steely Dan, George Benson, Return to Forever, and some dude named Pat Metheny.

Lacking the budget to buy all of this stuff - you couldn’t pay $10 a month to stream whatever you felt like back then, you actually had to pay for it, at a record store - I filed these names away and went back to listening to Rush, Led Zeppelin, Frank Zappa, Pink Floyd and BeBop Deluxe on infinite repeat.

And then I got my hands on that issue of Guitar World, which had grabbed my eye on the newsstand because of the Zappa article - ‘Frank Zappa: Genius or Junk Dealer?’ it asked, to which I replied ‘Genius, duh!’ - and lo and behold, there was the very guy Cousin Mike had gushed about, right on the cover, looking like a genuine rock star, which was not at all how I imagined jazz cats presented themselves.

I read the Metheny piece over and over again. I’d never heard his music, but the piece was very well-written, Metheny came off as erudite, enthusiastic, educated, and - most important to me, at the time - he just looked cool as hell. I fell for the guy without even hearing a note of his music.

It would take another 2 years before I could associate a sound with the image of that guy in the magazine. As a sophomore in high school, I somehow acquired the Pat Metheny Group’s double-live album, Travels. And by my first time through side one of that masterpiece, it was game over for me.

I had no idea what to call this music. It didn’t have a lifestyle attached to it. It was jazz, ostensibly, but it also rocked at one turn, went cinematic and esoteric like Pink Floyd at the next, and brought elements of African, Afro-Cuban and other multi-cultural sounds in and out of the mix at will. Metheny’s playing sounded like the heavens opening, but he was equalled in that department by the elegance and eloquence of his writing partner, pianist/keyboardist Lyle Mays, the nuanced strength of the rhythm section of bassist Steve Robby and drummer Danny Gottlieb, and the keening beauty of Nana Vasconcelos’ percussion and vocalizing. It was the imaginative universe summoned by the compositions and arrangements, and the transcendent quality of the improvisations and ensemble interplay, that exploded my preconceptions and opened my mind. This was some sublimely powerful stuff.

I’ve devoured everything Metheny has done in the time since - with the Metheny Group, as a collaborator with everyone from Gary Burton and Jim Hall to Ornette Coleman and Brad Mehldau, and as a solo artist. All of it has rewarded my attention and the investment of my time. And all of it has captured my imagination.

His latest venture, Dreambox, finds Metheny exploring yet another facet of his musicianship - it’s comprised of 9 diverse solo pieces for electric guitar, with minimal overdubbing of melodic material, all of which Metheny discovered rather randomly, hiding in a folder on his laptop.

Significantly, far from being a ‘guitar player’s album made for guitar players,’ Dream Box is a deeply moving, emotive affair that boasts the beautifully non-volitional logic of a dream state.

Metheny has taken to the road in support of this striking music, and he’ll stop at the Center for the Arts on the University at Buffalo’s North Campus for a 7:30 p.m. September 27 gig. I caught up with him a few days into the tour for this interview.

Over the years, I’ve seen you perform in so many different formats - from the broadly and beautifully orchestrated Pat Metheny Group, to a fiery quartet with Herbie Hancock, Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette, to the Orchestrion project, to the Unity Band with Chris Potter, to the recent Side Eye performances. I’m wondering how difficult it is to change hats for something as (comparatively) bare and intimate as the wholly solo performances you’re doing on this tour?

Man, you have been through it all!

This is in a different category, completely, in terms of a type of performance. Weirdly, ‘playing the guitar’ is about the 5th thing on the list for me, in terms of how I think of what my life as a musician is like, and has been, over the years. These evenings really require a focus on playing the instrument that, honestly, is kind of new for me, and in a way, that is one of the most exciting aspects of it all.

I have never really focused this closely on that aspect of things. Mostly, my thing has been about conception, band-leading, composing, and all, of course, with improvisation as the main center of it all, with the guitar functioning mostly as a translation device.

This tour is a look at all the ways that I have addressed ‘solo’ playing, and there are a lot of different aspects to the way that I have worked in that area over the years, along with everything else. But this time, that is the center of it.

One of the biggest challenges, actually, is the physical one of moving between quite different guitars, in terms of the scale of the various necks and so forth. But I am really enjoying it. I always like to be in situations where I don’t exactly know how to do it, and then have to figure it out as I go.

What is the conceptual through-line between all of these various incarnations of what you do?

I would say that the main thing is that I don’t see anything as being an incarnation - to me, it is all one thing. I often run into folks who are sure there are ‘side projects’ to something else, or that this part of my thing is more than that other part, and sometimes there are even quite strong - almost partisan - arguments between folks, and so forth.

If there is anything that I would hope to have addressed across all this time, it is to try to play the music that I love and to try to find the right sound and spirit to make each thing be what it seems to want to be. And it seems a lot of people identify that it is me, regardless of the setting. So I kind of take heart in that - that maybe the message might get through, across the years.

‘If there is anything that I would hope to have addressed across all this time, it is to try to play the music that I love and to try to find the right sound and spirit to make each thing be what it seems to want to be.’

You’ve said of ‘Dream Box’ that “dreams in their broadest sense make up the vibe with this set… Music exists for me in an elusive state, often at its best when discovered apart from any particular intention.” Can you describe how you are able to separate the part of you that is a detailed composer, arranger and orchestrator from the part of you that is able to tap into the intuitive, “intention-less” state of dream-logic that informs this music?

That is a really good question.

There are different stages along the way at every level, where the amount of effort that it takes to completely absorb the details of the task at hand to the point where you almost couldn’t-mess-it-up-if-you-try is required. For some of what it takes to address music at the level I hope to get to someday, that required period could be a lifetime. But sometimes it just means you have to practice the changes across those 4 bars a hundred or a thousand times. Sometimes it means you need to be around a good drummer. The different ways that that aspiration expresses itself are almost infinite per person.

Once you get to the point where you don’t have to think about it, then the possibilities start to expand in a kind of 360-degree way. And I think, to the degree that it is possible to aim for a kind of intuitive thing, you might be able to increase the odds of that happening with that degree of preparation. But there is never a guarantee of anything in music. Particularly in improvisation.

The way you discovered these pieces you’d recorded and forgotten on your hard drive while on tour feels like a perfect metaphor for the record itself - it’s as if they’re dreams you had that slipped back into your subconscious, but then somewhat randomly rose to the surface again. The album really does come across as a beautiful dream. Was there ever a temptation to flesh out and arrange these songs in an ensemble context? Was it difficult to just stand back and ‘let them be,’ so to speak?

This record is so unusual for me. It really kind of has a life of its own that I have not questioned too much along the way. That said, yes, I do think a couple of the tunes might be fine in ensemble settings. But unlike any other record that I have made, I really kind of took this for what it was and didn’t feel much of a need to change much about how they seemed to show up.

That said, because of the random way I recorded everything, the tech side of making the record work was kind of a challenge. But with the help of my long time engineer Pete Karam, somehow, we figured out how to make it all work together, despite the fact that, sometimes, I just turned the thing on without even looking at the levels, or whatever.

In a way, you’ve been tapping into these beautiful dream spaces in your music from the beginning - whether it was ‘Watercolors,’ or ‘New Chautauqua’ or ‘As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls,’ there has always been a strain of your music that feels like the soundtrack to that realm between being asleep and awake. Is ‘Dream Box’ part of a continuum, in that sense?

My own relationship to music exists almost totally within the realm of music itself. Honestly, I am kind of envious of folks who might be able to do what you describe there at will. I don’t seem to have the musical gene that allows me to do a kind of A>B thing. The closest that that requirement has come up for me has been film scoring, where you do your best to respond to the outside elements in a way that harmonizes or rhymes or works with the actions on screen.

When a project is done, I often drive around and listen to it. That’s the first time I ever allow myself the luxury of being a civilian in it all - and usually, only once or twice. I do have the capacity to completely - I mean 100% - turn off the musician in me. But it’s a bit like going underwater and holding my breath….I know I can do it, but not for very long . And it is kind of scary.

Can you discuss how important musical mentorship has been to you? It seems that you have, for a long time, been eager to work with musicians from different generations in formats that might be new or different for them, whether that was Antonio Sanchez in the beginning, or James Francies, Logan Richardson, Gwilym Simcock, Linda Oh and many others. What have you gained from these interactions?

I started playing professionally when I was 14 or 15 in Kansas City, and obviously, everyone was a lot older than me on those bandstands. I have continued to play and work with older musicians. Roy Haynes is now in his 90s, and we haven’t done anything for a few years, but he still sounds great. I am working with lyricist Alan Bergman on a set of tunes, and he is in that age range. That generation 10+ years or so older than me, right above mine - Gary Burton, Steve Swallow, Herbie Hancock, Jack DeJohnette, Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea and many others - was so exceptional and inspiring.

When I started my own band, I was with folks basically my own age, but there were not a lot to choose from. The generation immediately below me did not make any sense to me at all, with the suits and ties and playing for their parents more than their peers - the big exception being (saxophonist) Kenny Garrett. Then the Joshua Redman - Christian McBride - Brad Mehldau - Antonio Sanchez - Larry Grenadier crew came along, and finally, I found a new tribe. Actually, most of those guys came and found me.

Since that bunch, it has been the occasional person, more than a group of folks. But I listen to everyone out there all the time, and when someone sounds good to me, I often invite them up to my place to play.

The most important thing, though, is that basically, once the music starts, the issues of age and chronology dissipate quickly, and we all disappear into the thing.

Bravissimo. Jeff. How well I remember your reverence for Metheny from all those years of our working together. It's a wonderful thing when musicians interview musicians. Beautifully done.

Pat is the man! Heard a live recording of him, Jaco and Bob Moses from right around when BSL came out and my mind was *blown* - big fan ever since